Casper Brindle: Hypermodality

Curated by Mika Cho

Luckman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

September 29 to November 19, 2022

Brindle’s Hypermodality is a phenomenal experiment expanding the aesthetic experience of color, light, and form concomitant with space. The various structural arrangements of his forms, partly reminiscent of the Light and Space movement, evoke a new sense of reality— a reality that transcends beyond the material facets into emotions long buried by man’s logical and structural pursuits. Likewise, it is rare to see such simplicity projecting complex notions regarding both being and time. While Hypermodality focuses on his current work, the exhibit is pleased to include earlier productions of Casper Brindle to provide and ensure a sense of his aesthetic journey and stylistic continuum. – Mika Cho

A contemporary disciple of the 1960s & 70s Light and Space generation, Brindle too is intrigued by the sensory experiences triggered by color and light. His expansive paintings shift and morph as the viewer walks past them, compelling them to pause and begin to explore the enigmatic spaces of perception. Brindle has referred to the process in which he creates his works as trance-like, and one can’t help but notice the meditative quality these paintings induce. Born in Toronto in 1968, Brindle’s family relocated to Los Angeles in 1974, and he has called the city home ever since. Growing up surfing the beaches of LA’s coast undoubtedly made a profound impact on the artist. Brindle started painting as a teen and in his early twenties, he apprenticed for the pioneering Light and Space artist, Eric Orr. Casper Brindle’s work has been exhibited across the United States and internationally. His work is held in a number of prominent private and museum collections including the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation and the Morningside College Collection in Sioux City, IA. He is represented by the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica.

CASPER BRINDLE: SIGNS AND LUMINESCENCES

By Peter Frank

Casper Brindle self-avowedly carries on a tradition of transcendence. A second-generation Light & Space (and less directly Finish/Fetish) artist all but native to southern California (he moved here with his family from Canada at the age of six), Brindle has experienced the same atmospheric phenomena and encountered the same space-age materials his Light & Space predecessors did. Further, as a studio assistant to Eric Orr, Brindle was in direct contact with leading Light & Space artists from a relatively early age. Among the large and growing cadre of younger “perceptualists” (as Robert Irwin prefers to call them), Brindle is notable for his close regard not just for the tendency’s reliance on optical effect, but for the austerity of its formal language.

And it is in that formal language that Brindle poses the abstract, even metaphysical questions that give his art its particular presence and vitality. Brindle’s art turns our attention to its minimalist composition as much through as despite its luminous, disembodied color and pristine, machine-tooled surfaces. He does not set our eyes afloat in unvariegated light, but thwarts such an optical free fall, deliberately compromising the “ganzfeld” – the surrounding light ambiance – with strongly posited horizontal and/or vertical devices. These structural devices encourage our eyes to apprehend the visual field either as a recessional space or as a surface structure. Or both (in an especially intricate overlay of vertical on horizontal).

Notably, the elements that constitute the horizontal and vertical presences in Brindle’s paintings do not function equally, or at least in the same planar context. The horizontals are entirely incised or “drawn,” scored across panels whose otherwise pristine expanses of color are not simply interrupted, but disrupted, by the edge-to-edge horizon lines. The lines seem to punch a fold into the underlying expanses, a kind of double-recession whose upper and lower segments mirror each other. (This reading becomes even more complex with the presence of several horizontals.) Meanwhile, the much thicker but much more abbreviated vertical elements are physically projective, sculptural manifestations that reassert the facture, the materiality, of Brindle’s method. At the same time, they dazzle and bamboozle the eye with their incandescence. These elevated dolmen at once burgeon forth in relief and float out beyond the apparent surface plane of the paintings – sculptures? – as they dissolve in their own radiance.

Thus, Brindle’s verticals are doing one thing, or set of things, while his horizontals are doing another. In fact, the two forms are operating in mutually exclusive compositional, not to mention perceptual, contexts. Brindle does not set up an ongoing dialogue between vertical and horizontal works, or even between the verticals and the horizontals occurring in the same works; rather, he proposes the physical and metaphysical presence of each from the outset as contrasting discourses. This is not Light & Space, it is Light With Space.

We can’t avoid the spiritual dynamic, esoteric and otherwise, that inevitably pertains to the axial relationship of vertical and horizontal, and Brindle knows that. Indeed, it is that presumption, and its myriad interpretations, that he challenges. From the ancients’ quadratic division of the universe to the iconography of modern Christianity, the contraposition of vertical and horizontal functions as a fundamental principle. In particular, the elaborations of late 19th century neo-religious thought latched onto such a powerful formal dialectic, inspiring the emergence of abstract art. (Piet Mondrian, for one, regarded the horizontal factors in his Neo-Plastic paintings as female and the vertical as male.) Brindle does not discourage such thought per se, but he proposes a condition of perception in which each factor not only operates in, but helps establish, its discrete universe.

Unlike his modernist forebears, then, Casper Brindle does not propound the establishment or translation of an extra-visual symbology. He presents basic formal, and perceptual, phenomena as themselves. A line is a line; an aura is an aura; they have meaning only as they affect us optically. The transcendence possible in and from the viewer’s experience of Brindle’s work is not promulgated as a spiritual response but as a perceptual one. Of course, the perception of such formulations, and especially of their seemingly magical conjuration, can lead viewers to epiphanies of many kinds. But what Brindle seeks to demonstrate is a kind of artmaking that is as direct and common, universal and self-referential as a sunrise or a seashore, an artmaking that goes back to the origins of aesthetic regard.

Los Angeles

August 2022

MODERNISM HANGS TEN

By Mat Gleason

October 2022

There is an easy metaphor for what Casper Brindle has spent his career doing: Swimming against the current. This simple near-cliché underscores how uncompromising an artist must be to make the art they need to make, despite “current” trends. Looking at Brindle this way appropriately posits this artist as a man of the shore, a surfer, a seer of the horizon out beyond the breakwater, at repose on the sand knowing that infinity lies a few yards beyond the incoming waves.

A survey of Brindle’s recent work, HYPERMODALITY at Cal State LA.’s Luckman Gallery was gorgeously curated by Mika Cho. Here we saw the artist’s affinity for an eternal Modernism, unfettered by trendy demands washing ashore in the art world as fast as the next wave comes and drags them back to the deep beyond.

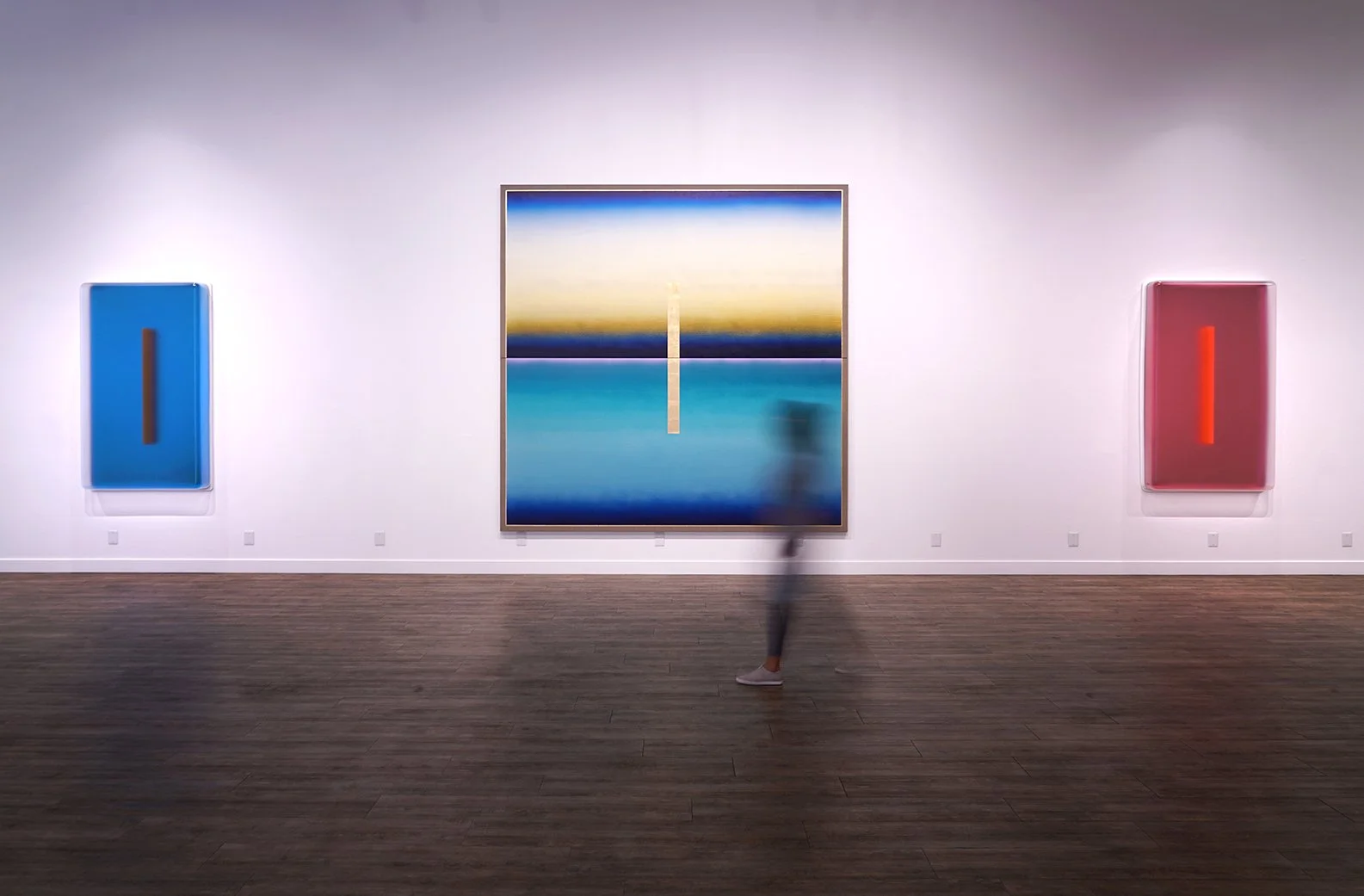

The exhibition deftly mixed a few large paintings on linen with many of his plastic signature style wallworks - paintings really, what the catalog calls pigmented formed acrylics. These are plastic-based homages to the Light & Space movement. The paintings on linen, though, firmly establish the connection Brindle’s practice has with High Modernism. In fact, much like a surfer maneuvering a challenging tide, Cho curates an artist navigating the territory where the sculptural objecthood of nontraditional materials smoothly nestles alongside Modernism’s heroic removal of painting from the dainty easels of yore. The accomplishment as seen at the Luckman Gallery is as bold internally as it appears smooth externally.

The subject matter of the Brindles here on display was consistent, if abstracted. The idea of a centerline is the basis of hanging most any contemporary exhibition, but with this artist the centerline is delivered vertically on the surface of the picture instead of horizontally on its backside. While no form in Modernism is without its predecessors, for all of his Light & Space pedigree, the association with the oeuvre of Barnett Newman is Brindle’s strength.

Yet rather than genuflecting in homage, Brindle wrestles with Newman’s core contribution to pictorial form, “The ZIP’ as Newman called it. Newman painted his Zip, a thin vertical stripe from top to bottom of his canvas, as a point of reference amidst what he called “the Sublime”. Brindle delivers his version of the sublime. The mellow bliss of the surfer exhausted after a day of conquering waves. The serenity of the luscious monochrome is only interrupted by a floating, perhaps anthropomorphic Zip.

In the Luckman Gallery exhibit these perfectly centered Zips do what Newman’s don’t… they submit to their surroundings. Brindle’s Zips don’t divide the composition, they are enveloped in it. The sublime, be it of an abstracted shoreline vista or a space with no physical boundaries, surrounds and embraces these sleek, sharp, lone forms. That the artist so perfectly centers each Zip in every picture gives the viewers the perfect vantage point to ponder both form and background.

There is a late (1953) Jackson Pollock painting entitled “Portrait and a Dream.” Although visually, with its tortured brushstrokes and rough figuration, it is antithetical to Casper Brindle’s core aesthetic, the midcentury masterpiece’s core contribution to the possibilities of painting was its compositional binary built on a visual and conceptual polarity. This approach to form (portrait) and setting (dream) is shared by Brindle. Over seventy years later, the living Modernist Brindle plays with this same conceptual energy here and now as Pollock did then, merely with different modalities - the portrait of the artist as a fabricator welded to the dream of pictorial space; the painter whose visual dream is achieved with materials beyond oils.

In HYPERMODALITY we have a curator in Cho revealing the artist as a surfer who knows the isolation after the long paddle-out and can manifest such a universal feeling of the natural sublime by adding a Zip to represent his presence in the vast field of nature - not quite swallowed up by nature but swallowing up the infinity inherent in the natural world.

In combining the visual binary drama of Pollock with the forms of the more minimal Newman, Brindle liberates the Zip from its tedious quest for the immortal. Free from this irrational burden of art history, Brindle’s centered form–be it a Zip or a zing, a surfer, a fin slicing the water or just an abstract urge; whatever it is defined as: this form centers itself in this veteran artist’s recent work to posit the viewer (with the artist being the initial viewer of his own creation) as central to any artwork’s existence.

Diversions LA

By Genie Davis

December 2022

If you were to pass from our universe to the next in a sudden flash of light and time, perhaps undergoing this passage through a wormhole, a dream state, or as they used to say on the bridge of the starship Enterprise, at “warp speed,” you might emerge transcendent, with a strange glow suffusing your vision. Such is the experience of viewing Casper Brindle’s mysteriously sensory art.

In a bravura exhibition at the Luckman Fine Arts Complex at CSULA, curated by Mika Cho, Brindle’s own passage through time, light, and space was on full and radiant display. Ranging from some works earlier in the artist’s career to a full focus on images created in 2021 and largely in 2022, Hypermodality provided a beautifully complete experience of Brindle’s work.

Dimensional images that pulse with color and light and play with perception are the core of Brindle’s work. His aesthetic moves the eye and the mind, vibrating with barely contained motion, hovering like a UFO just outside our peripheral vision. Both galvanizing and meditative, varying in color from vibrant shades to cloud like monochromatic shadows of varying hues, these works create emotional and cognitive leaps for viewers, bounding between shades and shadows, running into the sharp edges of horizon lines or disappearing like the taillights of an interstellar ship traveling an incomprehensible speed into a thick, floating tube.

Beautifully curated across two connected, open, large gallery spaces, wandering through the Hypermodality exhibition, which closed at the Luckman in November, was like floating on a life raft of light. Seeing these images in this serene space, it was possible to take in both the meticulously applied airbrushed layers of paint, the hypnotic quality of Brindle’s use of gradated color and shadow, and the enigmatic glow of the art.

The artist’s most recent work is so luminous that it appears to use external lighting, while in reality using color and texture to create an aura of soft, regenerative light.

Some works seem to bathe the viewer in bioluminescence, pulling the eye into a softly opaque sea or into the center of a soft cloud. Just as a bioluminescent sea shines when disturbed by a breaking wave, these works shimmer as the viewer moves closer or farther from them, whether they are viewed from the side or the center.

Other paintings recall the opalescent glow of a pearl, or the shifting colors and light flares of a fire opal. Indeed, each of these works could be pulled from the sea or the sky, or within a long-buried geode, cracked by time to reveal the shining gems within.

Uniformly, Brindle’s work is a perfect haiku of light, as well as an epic study of how color contains or expresses that light. Each piece tells a story of transformation, of how our vision of the world changes that world; how our eye creates the place in which our hearts and minds dwell, not just geographically but emotionally.

All this in works that are formal and made with careful attention to line, geometric principles, and a cool intensity of mannered shapes and patterns.

With titles that describe light glyphs and portals, it is no wonder that Brindle’s art evokes time travel, the speed of light, powerful entities and spiritual understandings, worlds that exist within or beyond our own comprehension.

An almost-holy simplicity infuses each work, whether created from pigmented formed acrylic or with layered automotive paint and gold leaf on linen. The impressiveness of Brindle’s technique rests in its quiet power, much as does the beauty of a sunset or the flare of a meteor. His art burns with the fire of color, and yet has an icy perfection that evokes a glass prism, capturing color and encapsulating it, allowing it to shift but not fade to black.

Some of the colors are startling: “Light Glyph VF 11” is the fierce cerulean blue of the hydrothermal Sapphire Pool in Yellowstone Natural Park. “Light Glyph VF 13” is the luscious tangerine of a citrus fruit on acid. Just as startling is the softly opalescent gold – with a layered burnt sienna orange bar at the center, or “Light Glyph VF 8.” The artist’s “Light Glyph VF 23” is no less riveting, an orange sun or a work with a softer, blurred orange bar at its center.

While each of these works are created using thick pigmented acrylic, Brindle’s works on linen are no less startling and rich, just differently textured. “Portal Glyph Painting X,” a massive 120 x 120 work using gold leaf and automotive paint on linen is an aqua sea and gilded sunrise with a glowing gold door cracked open just enough to see and allow passage if we dare.

A pair of sensual curves in hot pink wait succulently behind a wider passage in “Portal Glyph Painting III.” In this work, a radiant, slender rectangle of blue and gold light features a dark gold bar at its center, a portal within a portal, perhaps.

Regardless of format, Brindle’s work is above all else alive. It is alive with light, alive with line, holding within its serene and pristine depths a seething, swimming, sensorial swarm of color. If the images deliberately create a sense of the possibility of passage, or entering an “other” realm or experience, then that passage is as the viewer wishes to shape it, leading where the viewer wishes to enter. The artist offers the portal to enter, or the light to step through, but it is up to the viewer to take that step.

One of the finest exhibitions of 2022, Hypermodality commands viewers to take action, to truly see what lies beneath the surface of art, and perhaps, life itself.